Macquarie Business School

The challenge

Creativity leads to innovation and competitive advantages in a globalised world. On what basis can governments and other funding bodies make decisions about art, culture and heritage investments?

Research Impact Summary

- The Australia Council has used the research to make decisions about financial support to artists and the development of programs related to literature and reading

- The research informed Australia’s national cultural policy as set out in Creative Australia, 2013

- Organisations like the National Association for the Visual Arts, and the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance, use the research to make policy recommendations to the Australian Government

- The World Bank uses the research methodology to evaluate the economic, social and cultural impacts of heritage-led investments in developing countries.

The Research

The value of art and culture is inherently subjective, yet policy makers must still make decisions about how, and how much, art and art-inspired industries contribute to the economy. Professor David Throsby has spent almost two decades helping policy makers understand and assess culture and heritage investments.

Throsby faced many initial dilemmas. In one article, Throsby says, ‘cultural content has no immediately obvious unit of account.’[1] So how can its value be measured? For example, advertising requires creativity but is it on par with music or literature? And the plot of a novel or play may suggest ideas for a video or computer game but how can the relative value of each be determined?

Throsby writes: ‘Borderline cases will always arise. For example, how should one classify a writer, such as a journalist, or a craftsperson making production runs of pottery items? Moreover, some cultural outputs – for example in theatre, television and film – are produced by teams, where the creative input is diffused across all members of the group including those whose occupations may not be obviously creative in nature’. [2]

Concentric Circles Model

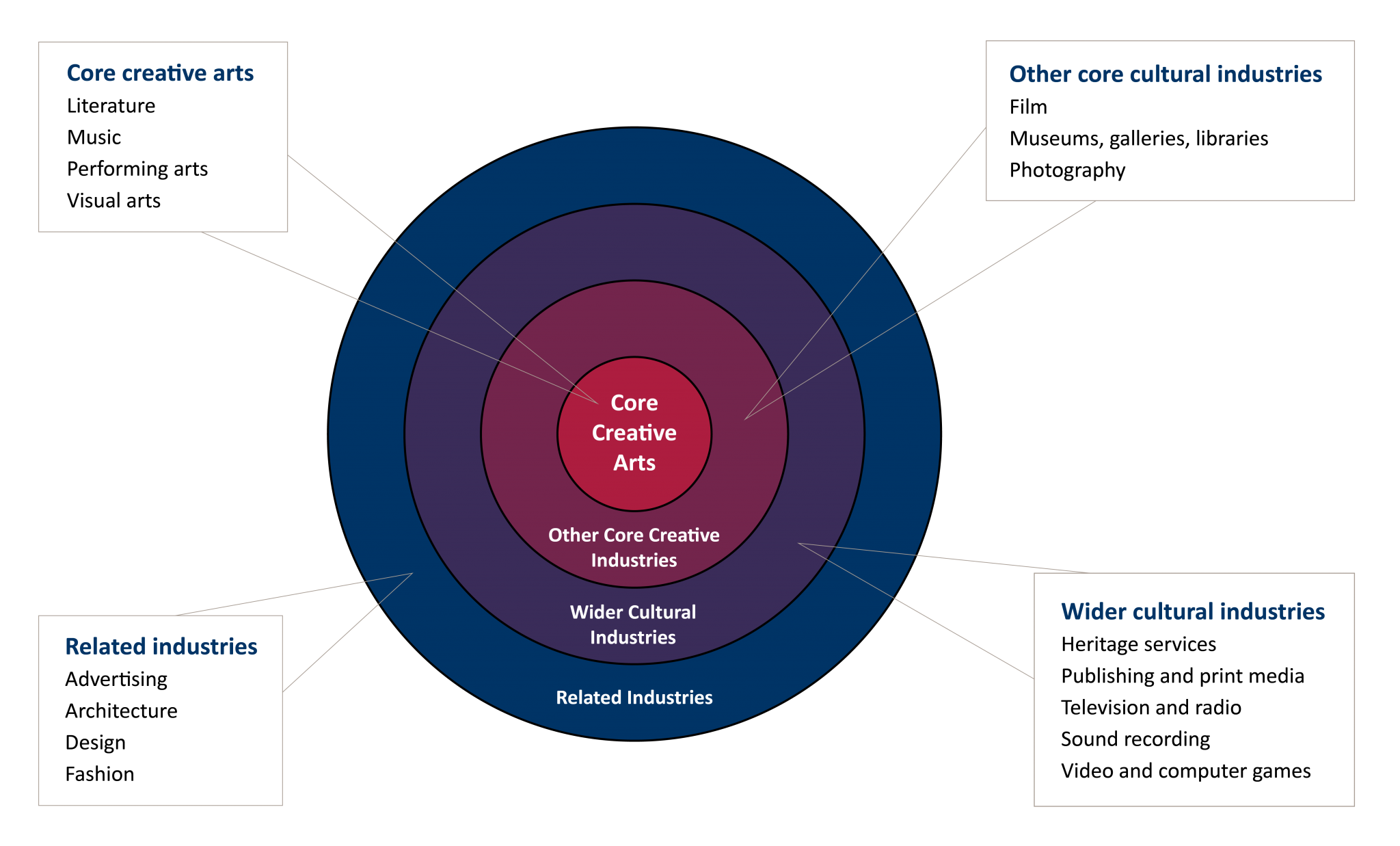

Throsby understood that the lines could be drawn in myriad ways and each would yield a different result. But one crucial element was to devise a coherent starting point, or framework – one that can describe the relationships between various arts and art-related segments of the cultural economy. The ‘concentric circles model’ (below) was the result

While acknowledging that there is no right or wrong way to model cultural industries, Throsby says, ‘the appeal of the concentric circles model lies in its emphasis on primary creative ideas as the driving force that propels the cultural industries and that distinguishes them from other industries in the economy. This basic characteristic helps to link economic and cultural analysis of the creative sector.’ [3]

The value of arts and the industries that rely upon them can be measured by pairing the concentric circles model with empirical data from, for example, surveys of artists and census data.

SURVEYING INDIGENOUS ARTISTS

One survey of Indigenous artists in Arnhem Land was designed to measure the economic importance of art and cultural production to the economic sustainability of remote communities in the region. Its success led to a similar survey of Indigenous artists in the Kimberly region of Western Australia and ultimately to the formulation of a National Survey of Remote Indigenous Artists.

Ongoing research-based surveys of practicing professional artists in Australia, undertaken every five to seven years, have been directly incorporated into the Australia Council’s strategy to support Australian artists.

While the research has assisted policy makers in Australia and internationally, it has also had a direct effect on particular cultural and economic sectors.

Australian Authors up to Global Challenge

Throsby and others, in a three-stage study of authors, readers and publishers, showed that Australian writers are proving equal to the challenges in global publishing, albeit with uneven distribution of financial rewards. The research helped the Book Industry Collaborative Council to write a blueprint for industry reform and make recommendations for the creation of an Australian Book Council.

Throsby’s related research on the role of culture in sustainable development was employed in the lead-up to the formulation of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals in 2015.

One of the other uses of the concentric circles model has been in UNESCO compiling national satellite accounts for culture. Satellite accounts are economic sectors that are not defined as ‘industries’ in national accounts.

When policy makers grasp the structure of cultural economies and how their parts fit together, the investment decisions they make are more likely to have the intended impacts. Artists and downstream industries are the direct beneficiaries but, in the end, their cultural and commercial contributions help sustain entire economies.

Share

Explore our other communications & learn more

We’ve collated all of our communications into the one place for your consideration, click one of the below buttons to explore each category.